Sept. 13, 1858 scared the bejeezus out of America.

John Price, an enslaved runaway, was living in a small college town on the outskirts of Cleveland when two professional slave catchers discovered his fugitive status. They contacted the U.S. Marshals, who obtained a warrant for Price’s arrest. The feds wanted to go in guns ablazing but the slave catchers knew better. They convinced the marshals to lure Price out of town with the promise of work. They forced him into a carriage and waited for the train.

Riding into Oberlin, Ohio, and snatching up Black folks was a crazy idea. The Fugitive Slave Act didn’t matter in Oberlin. Warrants were useless.

Everyone in Oberlin had heard James Bradley’s speech.

In 1834, Bradley, the lone Black student at Lane Seminary, participated in debate on abolition, colonization and whether America should ship emancipated Black people to Africa. All of the white abolitionists attended, including Lane’s pro-“go back to Africa” president, Lyman Beecher. Lyman even let his 23-year-old daughter participate, hoping it would inspire her to do something with her life. Owen Brown, a white abolitionist who built nearby Western Reserve College, was also there with his son. Brown had recently distanced himself from Western Reserve because he disagreed with segregation.

White abolitionists held these kinds of event all the time, but this time was different. They were in awe as Bradley told them about being kidnapped from Africa and trafficked to South Carolina. For two hours, he explained to all the white abolitionists all the things they were wrong about. He even lambasted the school president.

Lyman Beecher was so embarrassed in front of his daughter, Harriet, that he banned discussions of abolition at Lane. The students and the audience were so radicalized that the student body voted to do everything in their power to fight slavery. The speech transformed the entire community—Black and white—into a radical, abolition enclave where Black lives literally mattered.

When Lane Seminary banned students from talking about slavery, the Lane Rebels—a bunch of white students who were radicalized by Bradley’s speech—left Lane. Bradley also quit the college. Fortunately, Owen Brown was just elected to the Board of Trustees at Oberlin College, just across town. He invited Bradley and the Lane Rebels to transfer, which they did.

Although Bradley is often cited as the first Black student at Oberlin, by then, Brown had already convinced Oberlin to admit two Black anti-slavery activists, Charles and John Langston. The Langstons were natural leaders, who also kicked it with childhood sweethearts Lewis Leary and his wife, Mary, the first Black woman at Oberlin

The Learys were born free in North Carolina. But when slave catchers tried to kidnap Mary and sell her into slavery, they moved to Oberlin, and Mary became the first Black woman at Oberlin College. Another N.C. transplant and the fourth Black Oberlin student, John Copeland, was also part of the crew. Copeland was one of the most popular Black abolitionists in America. They even let Brown’s young son hang around as the team of Black and white radicals opened one of the most successful stops on the Underground Railroad.

So when the white boys kidnapped Price, the Langstons, Copeland, the Learys, the Lane Rebels and a group of radical abolitionists mounted up. They told the trustee’s kid to go home and they went looking for the slave catchers.

The Oberlin Heritage Center writes what happened next:

John Watson, a black store owner in Oberlin, arrived in Wellington first. Soon between 200 and 500 men crowded the streets around the Wadsworth Hotel where the slavecatchers held Price. The crowd began to shout back and forth with the captors, disputing the legality of the capture and demanding to hear from Price himself. Many in the crowd were determined to free Price, whatever the law or consequences.

Charles Langston, a black school teacher, moved through the crowd trying to calm the armed protesters. When the southbound train arrived, the situation grew urgent and the crowd began to force their way into the hotel. In the confusion that followed, Price escaped with the help of men who had been trying to negotiate with the captors. Energized by the success of the rescue, Oberlin residents paraded back from Wellington, “shouting, singing, rejoicing in the glad results.”

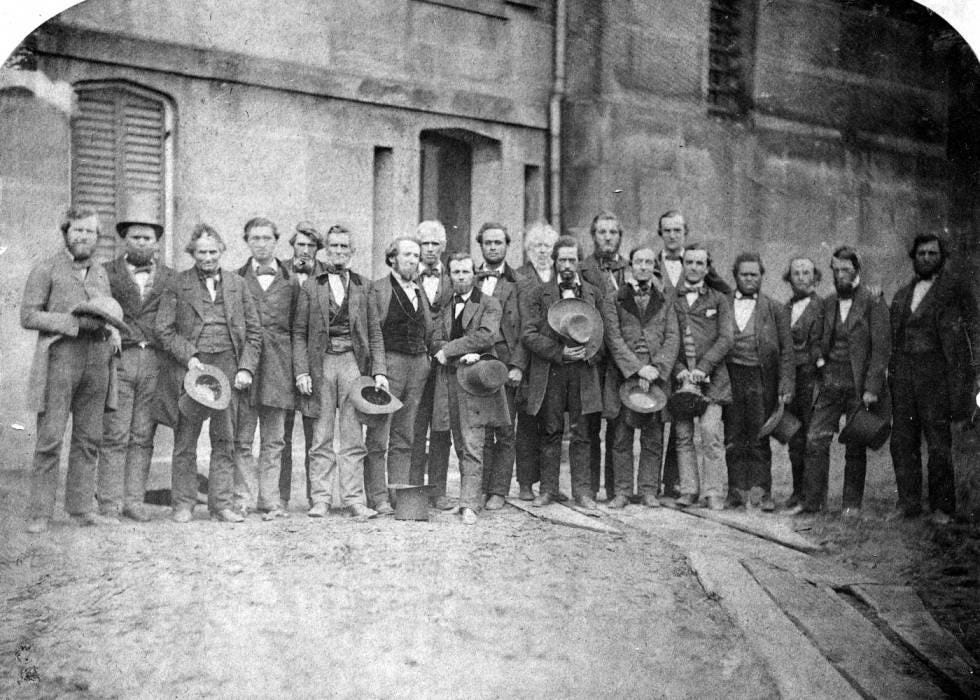

U.S. Marshals indicted 37 of the protesters who participated in the Oberlin Rescue for violating the Fugitive Slave Act. However, afraid of another multicultural uprising, the government only convicted two men, Charles Langston and a white abolitionist. Nearly 10,000 people showed up to protest the conviction, When giving the men the lightest sentences possible did not appease the radical town, the government basically gave up and freed them before their sentences were completed. Then, the residents ran the judge out of politics.

When Charles returned to Oberlin looking for his homeboys, no one was around. His brother, John, was off recruiting Black soldiers for the Civil War. John would later serve as the founding dean of Howard Law School, the first president of Virginia State University and one of the first Black Virginians to serve in Congress.

Mary Leary had gone to live with her parents. Her husband, Lewis, left town with Copeland when she was nine months pregnant. They said they was going on a “mission” with the little white trustee’s son. Apparently, the little kid was all grown up and had become a preacher. Mary eventually discovered that her husband, Lewis, John Copeland and the little trustee’s kid had been killed in Virginia. The newspapers would later call the incident “the first battle of the Civil War.”

As the Civil War erupted, Mary and Charles Langston married, moved to Kansas, bought a farm and started teaching self-emancipated slaves at the first contraband camp west of the Mississippi River. After the war, the couple moved to Lawrence, Kansas, and founded Western University, the first HBCU west of the Mississippi. While they focused on training teachers, they raised two children, Nat Turner Langston and Caroline Langston. Charles Langston died in 1892, and his daughter married and became a schoolteacher. When she divorced, she sent her only son, James, to live with his grandmother Mary.

Using oral tradition, Mary taught her grandson about his grandfather. She told James about their abolitionist days and the Oberlin Rescue. She told him about Lewis Leary and John Copeland. She told him about their days on the Underground Railroad and their college days. She told him about the trustee’s kid. And of course, she told her grandson about the speech.

“Through my grandmother's stories life always moved, moved heroically toward an end,” James later wrote. “Nobody ever cried in my grandmother's stories. They worked, schemed or fought. But no crying.”

What does any of that have to do with Don Lemon?

It would be easy to attribute the Oberlin Rescue, the Underground Railroad and the entire Civil War to one speech. The truth is probably simpler. According to historians, James Bradley’s speech was “the first instance in the history of the United States that a Black man addressed a white audience.”

And look what happened.

Literally the first time white people listened to Black people, America was changed forever. We got Black leaders, three HBCUs and a Civil Rights Act. The Lane Rebels became prominent ministers, politicians and reformers and part of the group that freed the Amistad survivors. The speech inspired Lyman’s daughter, Harriet Beecher Stowe, to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. When Lincoln met her, he said: “So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war." And remember the trustee Owen Brown's son, who was killed on that “mission” with Lewis and John Copeland?

That was John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

John Brown didn’t radicalize Black people; we radicalized a little kid named John Brown. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel radicalized white people. But the first Black person she ever heard radicalized her.

This is why they want to silence Don Lemon:

Donald Trump is not afraid of Lemon. He is afraid of the truth. He is afraid that it can inspire a true, multicultural movement.

He is afraid of you.

As Mary and Charles’ grandson, once wrote:

Freedom will not come

Today, this year

Nor ever

Through compromise and fear.

I have as much right

As the other fellow has

To stand

On my two feet

And own the land.

I tire so of hearing people say,

Let things take their course.

Tomorrow is another day.

I do not need my freedom when I’m dead.

I cannot live on tomorrow’s bread.

Freedom

Is a strong seed

Planted

In a great need.

I live here, too.

I want my freedom

Just as you.

– "Freedom" by Langston HughesDo not compromise or fear. Work, scheme, fight and move heroically.

But no crying.

Today’s Reading List: