This interview originally aired on the June 23, 2013 episode of “The Black One” podcast.

It was the cheeseburger that did it.

In 1958, police officers in Richmond, Va., arrested Bruce George Washington Carver Boynton for sitting in the “whites only” section of a Trailways bus station. They were appalled by the arrogance of a 21-year-old Black man casually flouting Jim Crow segregation while demanding that a white person fix him a cheeseburger.

The cops who charged Boynton with trespassing probably had no idea that Boynton was traveling to Selma from Washington, D.C., during his Christmas break from Howard University Law School. They probably didn’t find out that Bruce was the son of legendary voting rights activist Amelia Boynton — the lead organizer of the Selma to Montgomery marches — until Bruce showed up in court with his mom’s attorney friend …

Thurgood Marshall.

On Dec. 5, 1960, the U.S. Supreme Court issued Boynton v. Virginia. The court’s 7-2 decision didn’t just overturn Bruce’s trespassing conviction; the justices determined that the racial segregation on public transportation violated the Interstate Commerce Act. The decision essentially desegregated all interstate public transportation, including waiting rooms, bus terminals and train stations…

But not really.

Most historians will readily acknowledge that interstate transportation remained segregated after the Boynton v. Virginia decision. Even white history buffs will concede that bus terminals and train stations were forced to integrate by the Freedom Riders — a multiracial coalition of civil rights activists who rode buses across the country to expose the criminals who were illegally enforcing Jim Crow apartheid. The Freedom Rides officially began on May 4, 1961 …

But not really.

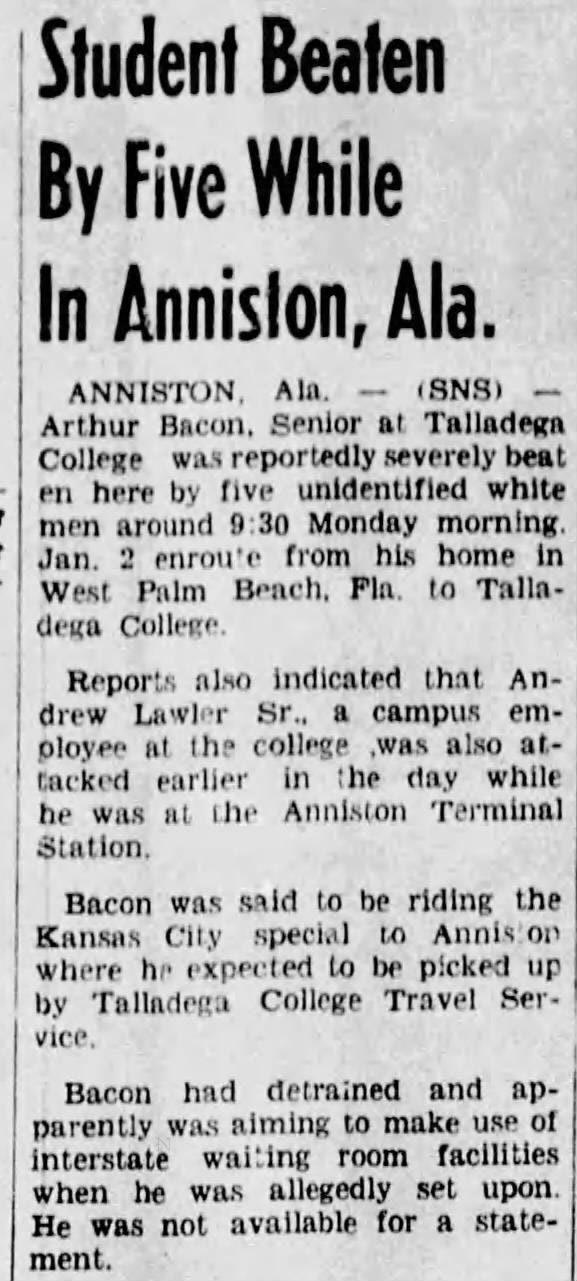

On Jan. 2, 1961, less than a month after the Supreme Court decided Boynton and four months before the Freedom Rides’ official start, Amelia Boynton picked up a copy of the Selma Journal and read the story of Art Bacon.

Two days after Bacon was “set upon,” his schoolmates at historically Black Talladega College went to the police station to demand justice. The cops had already arrested one of the perpetrators, but the students wanted more. And, unlike the Freedom Riders, these HBCU students had not been trained in the strategy of nonviolent resistance. So when the racial terrorists showed up again, the students didn’t ask for peace and reconciliation.

They wanted a rematch.

“Fighting between white persons and Negroes broke out in front of the Anniston police department today in the wake of picketing by Negro students,” the Associated Press reported. “Police said that three or four white persons and one or two Negroes actually fought while a crowd numbering more than 100 white persons and almost 100 people looked on.”

According to Chief J.L. Peek, the Black students were arrested because they were armed. And after Peek’s officers misplaced the evidence against Bacon’s attackers, an all-white Calhoun County grand jury refused to indict the white man who was arrested for beating Bacon. To be fair, after dropping the charges, the grand jury suggested that Peek’s officers “be most diligent in the securing of evidence and all acts concerning cases of this type.”

While the incident known (to me) as “The Real Bacon’s Rebellion” undoubtedly inspired the groundbreaking civil rights journey, the young Freedom Riders naturally assumed that the older, more well-known civil rights activists like Martin Luther King Jr. wouldn’t participate. King claimed he was already on probation, but some people speculated that joining the radical movement would jeopardize King’s connection with Robert F. Kennedy, who often shared information with King.

“We just couldn't understand why we would go, and he wouldn't go,” explained the late civil rights leader Julian Bond. “The excuses he offered didn't seem to make sense to us. This was the beginning of some disillusionment with him, and some feeling that he wasn't quite the guy we thought he was. We loved him, but he dropped slightly in our estimation of him." But by the time Bond and the Freedom Riders reached Atlanta, they had found their answer:

Art Bacon.

King had read about Bacon. According to another Freedom Rider, when King dined with the group in Atlanta to celebrate them reaching the halfway point, King revealed the source of his hesitancy.

At the meal that night with Dr. King, the group raised toasts honoring the completion of the first seven hundred miles of their journey. I later learned that after all those toasts, Dr. King took aside Simeon Booker, the reporter from Jet Magazine who was traveling on the Trailways bus, and whispered to him:

“You will never make it through Alabama.”

He was right.

On Mother’s Day, Anniston law enforcement officers watched and did nothing as 100 Klansmen bombed a bus containing Freedom Riders. Peek, the Anniston police chief who arrested the Black students for retaliating against Bacon’s attackers, “pointed out that if the travelers hadn’t come here, there would have been no trouble.” The next day, Birmingham Police Commissioner Bull Connor allowed the Klan to attack the Freedom Riders again. And because the law enforcement agencies were not “diligent in securing evidence,” no one was even charged for the acts of domestic terror.

King’s prediction was true, but he wasn’t afraid.

While King was pastoring at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, the same Klansmen who attacked the Freedom Riders had bombed King’s home, so he did not fear Bull Connor or the KKK. After Amelia Boynton, Thurgood Marshall and John Lewis all told King about the story of Art Bacon, he discovered that Connor and the KKK were planning a similar terror attack on the Freedom Riders. King was not offering an excuse to the Freedom Riders at that Atlanta dinner; he was trying to warn them what was about to happen.

Following the incidents, a local judge issued an injunction prohibiting the Freedom Riders from entering the state of Alabama. Defying that order meant King would have violated his probation, almost certainly resulting in the most important figure in the fight for equality receiving a lengthy jail sentence. Had King been on that bus, he certainly couldn’t have persuaded Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to send the National Guard to protect the Freedom Riders. But the injunction didn’t have anything to do with King, Connor or the civil rights movement.

It was about Art Bacon.

Alabama’s attorney general filed that injunction on behalf of the men who witnessed the Bacon incident and were afraid Black people would return the favor. The cowards’ identities were confirmed by the Anniston Star five days after the Aniston attack:

“A copy of Judge Jones’ injunction has been received by Anniston Police Chief J. L. Peek and Calhoun Sheriff Roy Sneed, they reported today.”

And it all began with Art Bacon, the first Freedom Rider who got his lick back.

Art Bacon graduated from Talladega in 1961 and went on to receive a Master’s and Ph.D. in zoology from Howard University. After becoming the first Black postdoctoral student at the University of Miami, Bacon went on to discover new species of protozoa. Then he became a world-renowned artist. Then he became the provost of Talladega College.

To be fair, the men who attacked Bacon also accomplished a lot. It turned out that one of Bacon’s attackers, Kenneth Adams, was one of the most violent racists in American history. In 1956, Adams led an attack on Nat “King” Cole. He organized the burning of over 100 KKK crosses and bombed a synagogue. He founded the “Original Ku Klux Klan of the Confederacy” and murdered at least one man. Two weeks after Bacon was attacked, brand-new Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy learned that the Klan was planning “a full-scale military operation,” starting with an assault in Anniston, followed by “mop-up action” in Birmingham.

To “help out with the welcoming party,” they enlisted Kenneth Adams.

It was Adams who was released because of a lack of evidence in the Bacon attack.

Then, in 1969, Adams was arrested, convicted and sentenced to prison for shooting 18-year-old Albert Lee Satcher. The FBI knew he was responsible for the attack on the Freedom Riders, but again, the Anniston police department mysteriously lost the evidence. The reason Satcher was able to identify Adams was that one of the Talladega student protesters was actually arrested for punching Adams in the mouth. The student was convicted because, somehow, the Anniston police department had not lost that piece of incriminating evidence.

That’s why Adams was identified for the attack on the Freedom Riders in Anniston. That’s also how we know Adams assaulted the activists in Birmingham. Violence is never the answer. But if those Talladega students were nonviolent, one of the most violent terrorists in American history would have never been convicted.

We always get our lick back.

Art Bacon passed away in 2023. But you can still listen to his story.