Primary Sources: The Secret Slave Revolt That Started the Civil Rights Movement

The story of the Underground Railroad, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer and Emmitt Till begins with a national slave revolt.

Instead of untold stories from Black history, ContrabandCamp’s Primary Sources series shares pure, uncut and rarely told stories from the past straight from the primary source.

Some stories don’t need whitewashing.

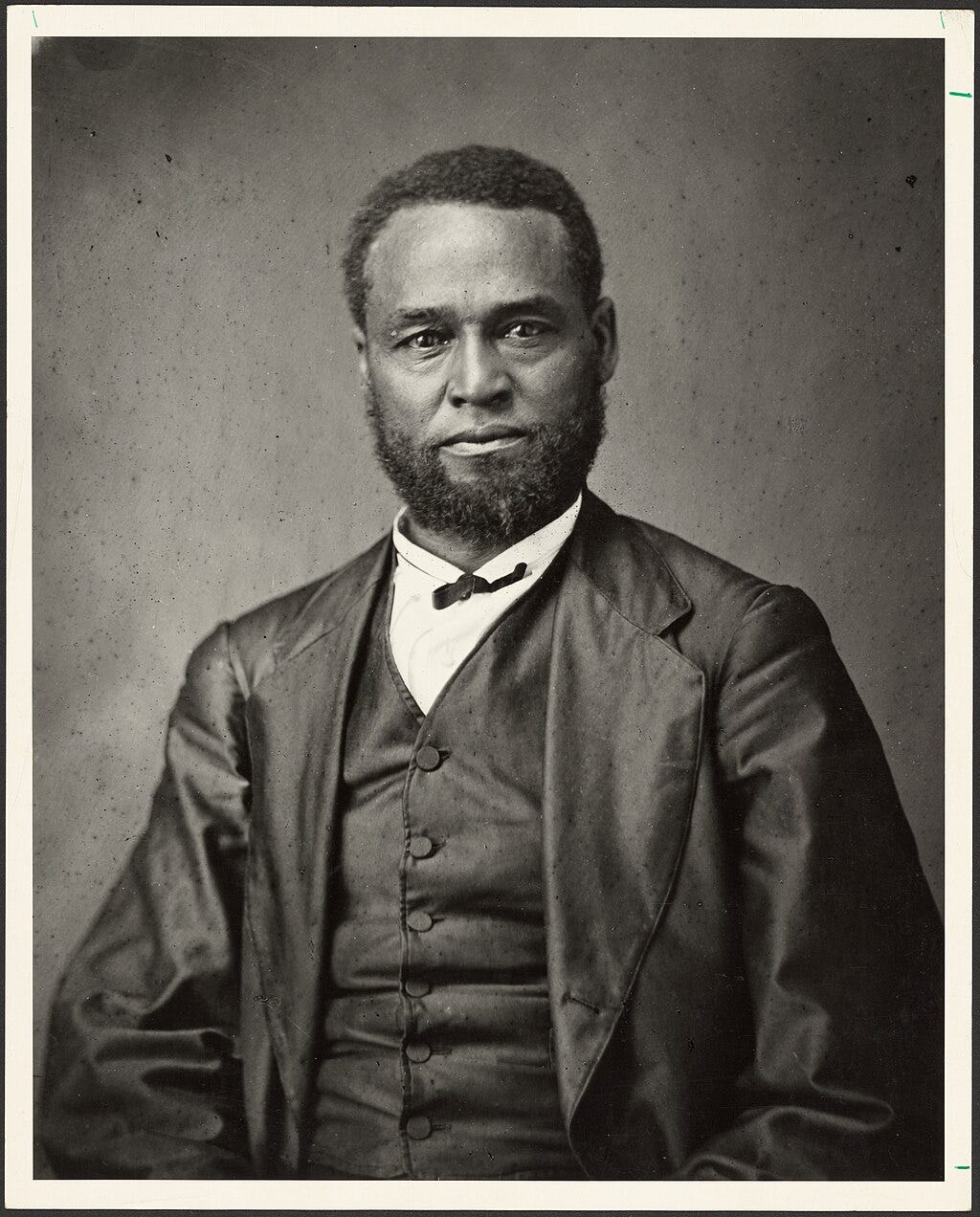

Of all the stories of Black history, the story of Moses Dickson might be the greatest untold tale of all.

Rev.…